UK pharma in “valley of death” as investors flee

Early-stage financing of pharmaceuticals and biotechnology has nose-dived in recent years, sparking concern that Britain could be wasting its opportunity to lead the world in medical science. Critics are quick to blame venture capitalists for refusing to invest on grounds of high risk and diminished returns – but is this justified?

In a 'knowledge-economy' where intellectual capital is equally, if not more, important than physical capital, it seems odd that success should rely on professional investors, whose main objective is to make money. However, without cash, science does not translate into marketable products, leaving experts and the media to talk of a "valley of death" between basic science and high-end pharmaceutical development in the UK.

The Guardian newspaper reported last year that more than a third of listed biotech firms went bust between 2008 and 2011, with 10 further companies struggling to stay afloat. At the same time, unquote" research shows the pharmaceuticals and biotech sectors have seen a fall in activity since 2007 that they have never recovered from.

Are venture capitalists turned off by high risk and diminished returns?

According to the media, the government, charities and venture firms are less willing to spend their capital on bets such as early-stage drug development because of the high risks involved and the poor returns these can entail. But David Porter, managing partner at Apposite Capital, a firm that specialises in investing in health care, says there is more to the funding gap than meets the critics' eye: "The support from LPs is a lot stronger in healthcare buyouts than it is in the early-stage venture. Partly that's a reflection of returns and partly this is because there are a lot of changes being made to the pharmaceutical model at the moment. It's difficult for people to get a feel for what's going to be the development of early-stage life sciences companies going forward, and that is causing some confusion."

Big pharma's R&D model is changing from a "do-it-all yourself" or "invest in high-risk binary companies" approach to a model that allows for more diversified outsourcing and more corporate venture partnerships. "On a longer view, this should be very good for early-stage life sciences companies, as big pharma will probably make less of their own compounds and buy more from other biotech companies", says Porter, "but maybe more changes will need to be made to how the biotech model works first."

Susan Searle, CEO of Imperial Innovations, a company dedicated to bridging the gap between science and commercialisation, says the industry has already moved on: "I think the model has changed. The days of people investing large amounts of money to build laboratories and do huge amounts of chemistry and science within start-ups have moved on, and a lot of the work is done in universities building on the work and expertise that's already there."

Investors nowadays are quick to distance themselves from the traditional high-risk binary biotech model – the all-or-nothing approach to developing drugs – that has been blamed for the downfall of a number of companies. Instead, they focus on the idea of de-risking their inherently risky industry. Searle explains: "What we've developed is a way of moving things forward quite capital-efficiently, so in the early stages, when we are developing things, we don't put much money to work. It isn't really until we get to the point where you've got a proposition that looks very viable, that has a good team around it, that we start to raise and put significant sums of money to work." She adds: "There's always a risk that therapeutics will fail, that's just the nature of drug development, but if you develop things from an early stage then what you get is an insight as to how things are operating. You can then bring that risk factor down."

Searle believes in the merits of working with experienced people, and says her firm gets LP support because it does a lot of early work on business and demonstration and ensures it brings in a top management team. She also recognises this as one of the key differences to now and 10 years ago. Asked about the general media outcry over a lack of venture funding in the sector, she simply responds: "I think they are a bit out of date quite frankly."

Imperial Innovations started out exclusively funding research carried out at Imperial College. The listed venture group has since branched out to other universities and research centres, and has so far realised a range of successful businesses, including RespiVert, a company focusing on the treatment of severe asthma, which was sold to Johnson & Johnson in 2010, generating a 4.7x money multiple for the fund.

Dismissing the widespread concern about a major problem with funding, Searle talks of a vibrant life sciences community in the UK which was successfully reignited by recent government, charity and private initiatives.

Government initiatives include the £180m Biomedical Catalyst, a joint project by the Medical Research Council and the Technology Strategy Board, which was announced in August 2011 and made its first two investments in August 2012. The public fund awarded £250,000 to Liverpool University's School of Tropical Medicine and £500,000 to the University of Manchester for early-stage research development.

New charity and government-backed funds have also emerged, most notably Cancer Research's cancer investment fund, which is backed by the European Investment Fund. Those funds exist alongside new corporate ventures and specialised venture capitalists, including the Wellcome Trust. "I think the life sciences policies are really paying off," says Searle. But it remains to be seen whether activity will indeed pick up and eventually bridge the gap between first-class science and commercial viability, helping the country realise its potential to be a worldwide market leader in the development of new drugs and biotechnology.

Latest News

Stonehage Fleming raises USD 130m for largest fund to date, eyes 2024 programme

Multi-family office has seen strong appetite, with investor base growing since 2016 to more than 90 family offices, Meiping Yap told Unquote

Permira to take Ergomed private for GBP 703m

Sponsor deploys Permira VIII to ride new wave of take-privates; Blackstone commits GBP 200m in financing for UK-based CRO

Partners Group to release IMs for Civica sale in mid-September

Sponsor acquired the public software group in July 2017 via the same-year vintage Partners Group Global Value 2017

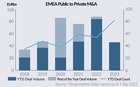

Change of mind: Sponsors take to de-listing their own assets

EQT and Cinven seen as bellweather for funds to reassess options for listed assets trading underwater