Start me up: the scope for investments in music

While many investments in the music industry appear to be paying dividends, the relationship has historically been punctuated by dissonance, as well as harmony. Kenny Wastell looks at the prospects for investment in the sector

Until recently, the most high-profile investment in music was Terra Firma’s doomed take-private for listed group EMI. The private equity firm acquired the music industry behemoth in 2007, in a transaction that gave the company an enterprise value of £3.2bn. The timing could not have been worse, however, with the music industry in the midst of a long-running battle against internet piracy and EMI itself posting annual losses of £260m.

The investment turned out to be on anything but solid ground, with Terra Firma eventually posting a £1.75bn loss on the asset and EMI entering administration in 2011. The private equity firm is still mired in an ongoing legal battle surrounding the deal, recently winning a retrial in its claim that Citigroup had fraudulently forced it to overpay for the asset.

An accusation often levelled at major labels such as EMI is that, following decades of booming record sales, the beneficiaries became too large and were unable to innovate in a changing consumer landscape. It is unsurprising that the most high-profile success story in the market today – Spotify – is a music-streaming service catering to a generation of fans that expects access to any song at any time.

As Fredrik Cassel, a general partner at Creandum (one of Spotify’s early backers), explains: "Rarely does real innovation within an industry come from incumbents. If we consider Airbnb, Uber and Amazon; these all benefited specifically from not being locked into traditional ways of reaching supply. Music is such a strong force in most people’s lives and a huge market, which can grow much further. Companies that manage to tap into this with a scalable business model will always be interesting."

In stark contrast to EMI, Spotify recently announced a fundraising round giving it a market cap of more than $8bn. This level of success from innovation – and dare we say "disruption" – is precisely the sort of approach venture capital players dream of. Spotify was by no means the first start-up to offer fans this type of access, with companies such as Napster, Pandora, Last.fm and Omnifone predating the Stockholm-based business. Nevertheless, it is impressive to consider a company launched less than 10 years ago is now going head-to-head with technology giant Apple to be crowned global king of digital music.

The rise of music-streaming services has not been without controversy. Years of negotiations between record labels and online start-ups have eventually resulted in platforms that offer unlimited legal access to extensive libraries based on freemium or monthly subscription models. "I think most of the music industry acknowledges that the $3bn Spotify has paid to rights holders since its launch is an extremely significant and important contribution," argues Cassel.

She works hard for the money

Yet debate remains as to whether artists receive a fair income from music streaming. Apple’s new streaming service, Apple Music, launched at the end of June to much criticism – not only from prominent pop star Taylor Swift, but also from the Association of Independent Music (AIM). AIM originally accused Apple of "asking the independent music sector" to "fund their customer acquisition programme", before the technology giant backtracked on plans not to pay royalties during its three-month free trial period.

With businesses valued at billions of dollars now dominating the consumer streaming market, the scope for venture investment in the segment is arguably decreasing rapidly. However, another undoubted linchpin of the music industry is the live market; an area that is somewhat less competitive, according to Saul Klein, who recently left his role as partner at Index Ventures. During Klein’s eight-year spell at Index, the firm invested in numerous music companies, including the aforementioned Last.fm. "When Last.fm was sold to CBS, our investment thesis changed from backing businesses where relationships with rights owners – labels in particular – were paramount to the success of the business. We shifted our emphasis to investing around a couple of themes; one such focus was live," he says.

"It became clear to us that the role of the record label was shifting profoundly – around 60-70% of revenue in the industry is now generated by the live performance market," Klein explains. "The reality is that recorded music is no longer where the money is."

Index recently invested in the merger of portfolio company Songkick – a personalised concert listings and aggregation platform – and Crowdsurge, which allows artists to sell concert tickets directly to fans. The firm had originally invested €3.6m in Songkick in December 2008, according to unquote" data. "The interesting aspect of the Songkick and Crowdsurge merger is seeing the two elements coming together," Klein says. "Crowdsurge focused on the supply side and sale of tickets direct from the artist; and Songkick focused on the demand side and a base of 10 million hardcore concert-going music fans."

We built this settee...

In a far more niche corner of the live market, Index has also invested in a start-up called Sofar Sounds – a promotional platform for secret performances by emerging and established artists that take place in people’s living rooms. Investments in this type of asset, with a unique concept offering, may point to the future of venture investments within the music industry.

Parminder Basran, managing partner at Velos Partners and formerly director of record label and recording studio Metropolis, points out some venture-backed start-ups themselves – in particular, crowdfunding platforms – actually challenge artists to reinvent their revenue models. "These have made bands and artists innovate in ways they have never done before," he says. "Artists have to now think of other ways to create revenue, which provides more purchase opportunities for fans. If you consider Pledgemusic, for example, it allows fans to invest in anything from live music to EPs in return for additional perks."

With regards to the criticism often directed towards labels – particularly concerning an inability to innovate – Basran counters by highlighting many larger music groups have started providing marketing and promotion services to independent artists and labels. In this way they are able to generate revenue from their core skills and networks, to some degree countering the impact from decreasing demand for physical distribution.

Of more direct relevance to institutional investors, Basran also notes Universal Music Group’s entry into corporate venturing as an important step in the evolution of the music industry. The development presents an interesting co-investment proposition for venture capital and private equity houses. "I think it makes sense for all the major record labels to have corporate venturing arms," he says. "Universal is up to something very interesting and we are very much looking forward to seeing how we can partner with them in future." Talent agency Creative Artists Agency also has a venture arm, which Basran points out is actively investing in the sector.

With streaming services fast becoming major music industry businesses themselves, co-investments and niche plays could well provide the most logical investment strategies for venture capital and private equity firms. It would certainly take hard work to convince limited partners of the logic in backing another EMI.

Latest News

Stonehage Fleming raises USD 130m for largest fund to date, eyes 2024 programme

Multi-family office has seen strong appetite, with investor base growing since 2016 to more than 90 family offices, Meiping Yap told Unquote

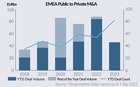

Permira to take Ergomed private for GBP 703m

Sponsor deploys Permira VIII to ride new wave of take-privates; Blackstone commits GBP 200m in financing for UK-based CRO

Partners Group to release IMs for Civica sale in mid-September

Sponsor acquired the public software group in July 2017 via the same-year vintage Partners Group Global Value 2017

Change of mind: Sponsors take to de-listing their own assets

EQT and Cinven seen as bellweather for funds to reassess options for listed assets trading underwater